Vaginal Health, Vaginal Microbiome

Just what is a “leaky vagina”? And why we should care about it…

I’ve just returned from the MINDD Conference in Sydney where I was invited to present lectures to both health professionals, and the general public, on the functions and importance of the vaginal microbiota.

One of the concepts I brought up at the conference was the idea of a “leaky” vagina. Many of us are very aware of the consequences of a leaky gut or leaky blood-brain barrier. But few of us have considered the concept of a leaky vagina – or what impact this may have on a woman’s health.

What are the known risks? Well increased risk of genital herpes infection, as well as human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and its sequelae cervical cancer, for two. Given this, I wonder why optimisation of the vaginal ecosystem is not a core component of a women’s preventative healthcare strategy.

The vaginal microbiota is the “poor cousin” of the GIT microbiota – it has only just begun to get the research interest it deserves. Research conducted over the last 5 years has clearly shown that an optimal vaginal ecosystem (i.e., an ecosystem dominated by D-lactate-producing lactobacilli species) is associated with enhanced fertility, better birth outcomes, and reduced risk of sexually transmitted diseases and recurrent urinary tract infections, as well as reduced HPV infection rates (a necessary precursor to cervical cancer).

So how many women have an optimal vaginal microbiota? Sadly, research suggests not that many – with some research finding only about 40% of women having ecosystems dominated by D-lactic acid-producing species (Lactobacillus crispatus, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii).

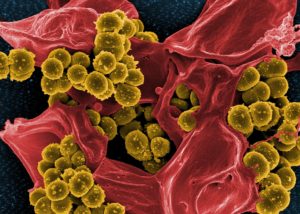

One final consideration is that we are only now finding out some of the ramifications of having a “leaky” vaginal wall. Other consequences will surely be teased out in the upcoming years. We know a dysbiotic vaginal microbiota containing large numbers of Gram-negative bacteria and a deficiency of lactic acid-producing lactobacilli leads to a leaky vagina. This is due to the vital role of lactic acid, specifically D-lactic acid, in the growth and repair of vaginal epithelial cells.

Undoubtedly, the combination of dysbiosis and increased permeability to bacterial by-products like endotoxins (from Gram-negative bacteria) will add to a woman’s inflammatory load. This may directly impact reproductory organs and contribute to diseases like endometriosis (see the paper on the bacterial contamination hypothesis below), but also have systemic sequalae. With inflammation now seen to be a key driver of most, if not all, chronic Western diseases, it is about time to highlight this issue. We know that GIT dysbiosis can contribute to systemic inflammatory load, but we now need to consider that vaginal dysbiosis can do likewise in women.

We, as clinicians, need to start assessing the health of this ecosystem in all of our female patients. A simple pH test strip (with accurate gradations between pH 3.5-5.5) is all that is needed for an initial screen for vaginal dysbiosis – with a pH >4.5 a clear indication of a dysbiotic ecosystem in pre-menopausal women.

To learn more about this vital, yet under-appreciated ecosystem, as well as learn techniques to optimise the vagina microbiome, have a look at our new course covering these topics (and more!).

Jason Hawrelak

ND, BNat (Hons), PhD, FNHAA, MASN, FACN

Chief Research Officer

Probiotic Advisor

Select References:

Borgdorff H, Tsivtsivadze E, Verhelst R, Marzorati M, Jurriaans S, Ndayisaba GF, et al. Lactobacillus-dominated cervicovaginal microbiota associated with reduced HIV/STI prevalence and genital HIV viral load in African women. ISME J. 2014;8(9):1781-93

Hyman, R. W., Herndon, C. N., Jiang, H., Palm, C., Fukushima, M., Bernstein, D., . . . Giudice, L. C.. The dynamics of the vaginal microbiome during infertility therapy with in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012; 29(2), 105-115.

Khan KN, Fujishita A, Hiraki K, et al. Bacterial contamination hypothesis: a new concept in endometriosis. Reprod Med Biol 2018;17(2):125-33. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12083

Kirjavainen, P. V., Pautler, S., Baroja, M. L., Anukam, K., Crowley, K., Carter, K. & Reid, G. 2009. Abnormal Immunological Profile and Vaginal Microbiota in Women Prone to Urinary Tract Infections. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009; 16, 29-36.

Mitra A, MacIntyre DA, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, Bennett PR, Kyrgiou M. The vaginal microbiota, human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: what do we know and where are we going next? Microbiome. 2016;4(1):58

Petrova MI, Lievens E, Malik S, Imholz N, Lebeer S. Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health. Front Physiol. 2015;6:81.

Younes, J. A., Lievens, E., Hummelen, R., van der Westen, R., Reid, G., & Petrova, M. I. Women and Their Microbes: The Unexpected Friendship. Trends in Microbiology. 2017;26(1), 16-32.

As a female and a swimmer, I would be really interesting to hear future applications of this topic such as environmental effects on the vaginal microbiome and “leaky vagina”. Looking forward to further research in this area as time goes on!

I think this is a fascinating topic and one that needs to be studied more and frankly, talked about. Women are shamed from talking about what is “normal” to our vaginas – even OBGYNs do not or choose to not talk about this important subject. Vaginal health is just as important a component as overall health and needs to be considered.

We need to empower women by educating them on what proper vaginal health looks like. Thank you for your post Dr. Hawrelak.

Yes, Brianna, definitely a topic that needs more awareness and discussion. A dysbiotic vaginal ecosystem increases a women’s chance of getting STIs, HPV infection, cervical cancer, fertility issues, and even poorer birth outcomes. How is this not an important topic to discuss and address! The ecosystem is easily modifiable to a healthy state (in most women) using the right tools and an imbalance is easily, simply, and cheaply screened for by assessing the pH.

Yes, we need to empower women around this topic and educate practitioners about its overall importance.

Thanks for this interesting article Jason Hawrelak – definitely a subject that needs to be discussed and spread!

I’m just wondering what the treatment would be once the pH assessment has been made?

Should we be suggesting the D-Lactic Acid-producing species you’ve mentioned here as a probiotic pesssary?

Or is there a ‘connection’ between the gut and vaginal microbiome – so adding the appropriate prebiotics to the diet would suffice?

And also the bladder microbiome.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/health/2018-06-03/bladder-microbiome-study-could-be-game-changer-for-uti-treatment/9822020

Really enjoyed part 1 of this course and looking forward to part 2. I wanted to enquire as to the ph test strips you recommend as I am having a lot of difficulty finding the appropriate vaginal ph tests strips with wider accurate ph range in Australia? Thank you for the amazing insights and cutting edge content.